Narrative Bunkers

The Manufacture of Truths Through an Excess of Knowledge Production

Today, group narratives seem to change faster than ever before while resisting change more than ever. It’s difficult to square the rapid fall of Liz Truss (abetted by abrupt abandonment by the previously exuberant Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph) with the ongoing persistence of seriously dubious narratives about the economy, COVID, immigrants, and so many others.

But for once, this paradox isn’t really a paradox. Narratives—in the sense of stories that social groups hold about the world and how it works—are ossifying because “facts” are generated faster and in greater volume than ever, and because the sheer amount of citable information has made it much easier to shore up the defenses any creaky narrative.

Prior to the information age, scarcity enforced conformity and narrative construction. Scarcity also permitted, when circumstances were right, quick narrative switching, since most narratives had a small elite of controllers who could, when the time was right, pivot and abandon a narrative that no longer made sense, was no longer convenient, or even had proven itself to fail to conform to facts (it did happen).

The internet has made non-academic knowledge production far, far more accessible and voluminous. This has occurred at all levels, whether highbrow, lowbrow, elite, anonymous, scientific, or nonsensical. The dislodging of the authority of “elite” opinion overlooks the fact that nothing has replaced it—or else that too much has replaced it.

There’s one area where this scarcity broke down long before the internet: academia—or at least parts of it. Long ago in 1903, William James bemoaned “The PhD Octopus” in 1903, ruing the standardized and professionalized requirements that academics had to generate scholarship whether or not the result was inspired or not. Usually, he observed, it wasn’t. One hundred and twenty years later, the problem has expanded by many orders of magnitude. In the 1950s and 1960s, the explosion in academic positions and the increasing requirement of college for the middle class led to an even greater boom in papers and books generated.

The effects of the research glut were often benign or at least reasonably contained, sometimes even beneficial. Scientific or methodological rigor sometimes triumphed; real discoveries sometimes rose to the top. But the more that money, prestige, and/or influence were involved, the more this expansion of “knowledge” production tended to generate unquestioned and dubious theses which were taken not as guidance but as gospel. A network of charismatic authorities, eminences grises, and outright autocrats guided academia. The requirement for new ideas, or at least that which appeared to be new, led to a more concentrated cycle of trend generation and parental slaying. But in the absence of severe competition (until the recent academic contraction), a surfeit of academic minicultures arose and coexisted—which was not such a problem unless the need for rigorously established truths arose.

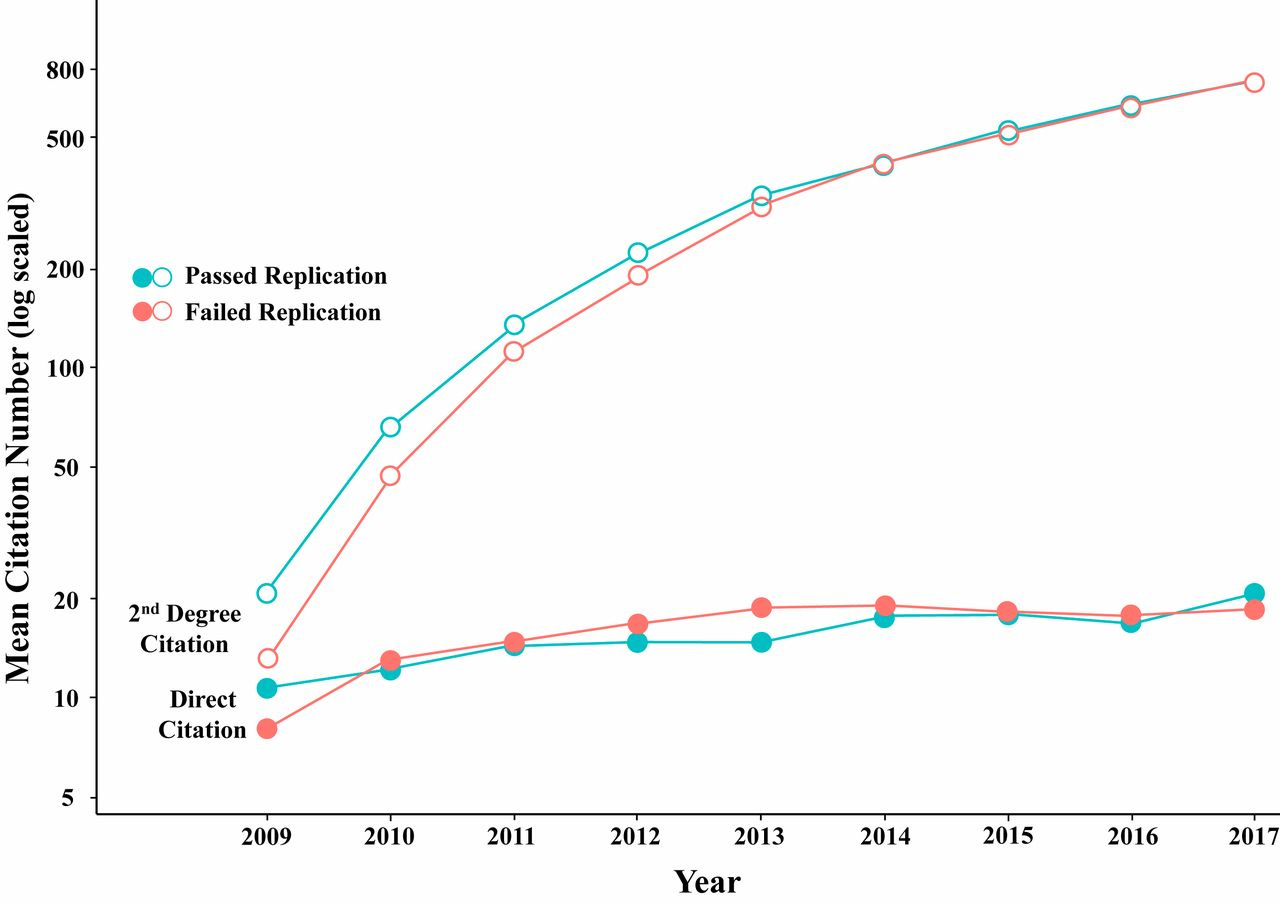

In the absence skepticism and outreach (understanding each other’s claims while questioning them), the mere act of citation is now cherry-picking. Over a decade after alarms over the “replication crisis” in psychology were sounded, New Scientist can only say, “The replication crisis has spread through science.” The Atlantic said in 2018, “Psychology’s Replication Crisis Is Running Out of Excuses.”

A 2020 study showed that citations of unreplicable and replicable studies were identical: there were no controls in place. I could not find whether that study itself has been successfully replicated, which gives some idea of the greater problem.

Such meta-analyses move the problem up a level: if multiple meta-analyses exist and don’t agree, you need a meta-meta-analysis to analyze the meta-analyses, or else once again you are cherry-picking (or independently synthesizing). In an environment of surplus instead of scarcity, there’s not even a need for adjudication of competing studies: everything coexists, and entities pick which ones suit their purposes through methods of greater or lesser integrity.

Instead of replications, however, you get overlapping studies where the metrics don’t necessarily agree. COVID brought this issue to the fore for anyone tracking the voluminous research being produced. The horrific finding published in Nature that a quarter of children and adolescents suffer long COVID after infection only holds if the rubric of “long COVID” brings under it kids who are merely “sad, tense, or angry” alongside those who have memory loss, hair loss, and constipation. The abstract only focuses on the 25% number, however, making it difficult to break down the study into signal and noise.

Surely there is some concrete ailment we can deem “long COVID” in the serious sense in which it is discussed as a major health event; by the graph above, it surely does not affect 25% of infected children and adolescents. The next meta-analysis which happens to push up to public consciousness may change that number, or maybe it will simply change the question being answered. But the process is not linear; it’s chaotic.

Only in remarkable cases where there is overwhelming consensus—say in the case of global warming’s existence (if not its trajectory)—can you be reasonably assured that you are citing something closer to a fact than a hypothesis. The difficulty is that in a world of an abundance of “knowledge” production, finding any dominant consensus becomes an act of research in itself—and convincing others of your assessment is another matter entirely.

We can look to academia as a precursor to what is now happening on the larger scale. There are two broad consequences:

Persistence of legacy narratives within established groups, which become increasingly blinkered and uniform. Members of groups resist going against prevailing narratives within your bunker: why buck your overwhelming crowd of peers?

Increasing lack of contact between narrative bunkers. There is little incentive for members to engage with other bunkers: why would you want your narrative to be threatened?

Narrative and knowledge scarcity forced some amount of pruning among narratives. Even if the “right” narrative didn’t win, the loser usually didn’t linger around as what Mary Douglas describes as a latent group (using Mancur Olsons’s term). In the online world of narrative abundance, there’s nowhere near such pruning pressure. Increasing numbers of narrative bunkers can coexist happily, less bothered by the need to compete with their brethren.

All bunkers are not created equal. Some will apply greater standards of rigor and skepticism; others will accept tenets of faith without question. But in all, the inertial force of the status quo within a narrative bunker holds significant weight because of the comparative absence of pressures against it.

There is still change in opinion and belief with narrative bunkers, but it occurs at the group level and not at the individual. Tipping points occur unexpectedly, not through something as idealized as rational discourse. If science only progresses one funeral at a time, narrative bunkers lack even those markers of change. To look at COVID narratives again, the enthusiasm or lack of enthusiasm for masks, vaccines, and remote schooling can’t be measured either through rational analysis or through top-down decision making. In retrospect, perhaps you can say that the overall shift in one group’s opinion happened at that time because of that phenomenon, but prediction is a rube’s game.

We are in a world of shifting masses of sentiment reaching tipping points at hard-to-predict times. The shift in sentiment of many Twitter epidemiologists in the COVID era is indicative. After their quick elevation to a happy perch of authority in 2020, many epidemiologists with tens of thousands of followers now complain about how politicians and institutions who’d previously Believed in Science™ have rudely abandoned it. Their complaints are justified overall, because the shifts in sentiment can’t be said to be justified by actual risk assessments or COVID statistics. But neither was the elevation of epidemiological opinion to prominence so justified either, as much as they like to think it had been.

Outside the realm of scholarly research, much the same holds, except further amplified. Development of prejudices, conspiracy theories, and mere everyday conceptual frameworks admits less and less modeling, predicting, or even simple description. The explosion of narrative bunkers is not yielding chaos, because the developments are not arbitrary even if they resist prediction. But narrative bunkers are lowering our ability to perceive the landscape of group belief as anything other than chaos—and perhaps that is not so different.