The Ascent of Lovecraft

Gnostic meaning in a time of chaos

H. P. Lovecraft was not on many people’s radar in the 1980s. He maintained a cult following in the horror community as a talented creator of a curiously antiseptic world of peculiar otherworldly beings and atmospheric New England horror tales, but you would frequently not find his works on the shelves next to Stephen King and Clive Barker. I found his purple prose to be off-putting, and whoever it was who said that Lovecraft spent more time telling you that you should be scared than he did actually scaring you hit the nail dead on the head. The story that Lovecraft cited as his model and ideal, Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows,” has a greater efficiency and elegance than Lovecraft ever managed. And the most famous adaptation of his work, Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator, is more an affectionately irreverent pisstake than a faithful tribute—likely because Lovecraft’s material is, at its heart, ludicrous.

And yet today Lovecraft is a solid pillar of the culture, with Cthulhu and the Elder Gods and the Necronomicon well-established horror tropes. Part of this is Lovecraft’s adaptability and the ease with which authors and creators elaborated on his lore after his death. Like Tolkien, he created (or at least repackaged) an exportable world full of “lore” that could be repurposed in part or in whole across movies, tabletop games, video games, comics, etc., where familiarity with one would act as an invitation into the others. Lord Dunsany, Mervyn Peake, R. A. Lafferty, and Lucius Shepard were better writers, but they did not build a single mythic edifice, instead dispatching fecund ideas as soon as the next one hit. Lovecraft was not as thorough in the creation of a single world as Tolkien, but he was good enough.

But that doesn’t explain why Lovecraft in particular, and why Michel Houellebecq, Alan Moore, and Mark E. Smith chose to inhabit his world so specifically, or why Lovecraft grew to so much greater prominence this century.

You can chart Lovecraft’s rise almost in direct opposition to the fall of science-fiction. There is very little of the sci-fi tradition left alive today, most of it having migrated into more literary realms or else taken the form of fantasy-in-space. Sci-fi as a space age product is more or less extinct, whether you’re talking about Arthur C. Clarke or J. G. Ballard. Which is to say that sci-fi served as both a myth and a critique of the Cold War, the space race, and above all, nuclear power. It was a product of a time in which society was confronted with intense destructive power placed into its own hands, with no authority to answer to other than our best and worst selves. There was little room for Elder Gods when the Day After showed us capable of ending the world on our own.

In 1967, the Chicago band H.P. Lovecraft wrote “The White Ship,” based on Lovecraft’s story of the same name.

The white ship has sailed and left me here again

Out in the mist, I was so near again

Sailing on the sea of dreams

How far away it seems

Sailing upon the white shipH. P. Lovecraft, The White Ship

It’s a classic, atmospheric song, but the atmosphere is melancholy and dreamlike, not the least bit scary. (The Farfisa organ and baroque harpsichord do not help.) Compressing the story to a lonely man (maybe) losing his mind, the song demonstrates how inapt Lovecraft was to the times. The band tried again with the also-great “At the Mountains of Madness” on their second album, and the results were even less haunting.

And then…it ended. Instead of the concrete reality of Mutually Assured Destruction, we got the amorphous forces of structural racism and late capitalism (or, if you were conservative, the clash of civilizations)—things that eluded being controlled or even described. As Kenneth Burke wrote in 1935:

For always the Eternal Enigma is there, right on the edges of our metropolitan bickerings, stretching outward to interstellar infinity and inward to the depths of the mind. And in this staggering disproportion between man and noman, there is no place for purely human boasts of grandeur, or for forgetting that men build their cultures by huddling together, nervously loquacious, at the edge of an abyss.

Kenneth Burke, Permanence and Change

The 1930s were the postwar time of chaos, of the popularity of Weird Tales, of economic and political chaos seeking order. And order was found with war and holding the power of annihilation in our hands.

Then the Cold War ended, and the void returned. Into that gap flowed chaos, confusion, blatant incompetence, and endless triviality, like writing troll memes on bullet casings used in a political assassination. When demon names like Monsanto and Blackwater fade away and we line up to proclaim ourselves “Team Pfizer” because Big Pharma seems no more threatening than any other bit of chaos.

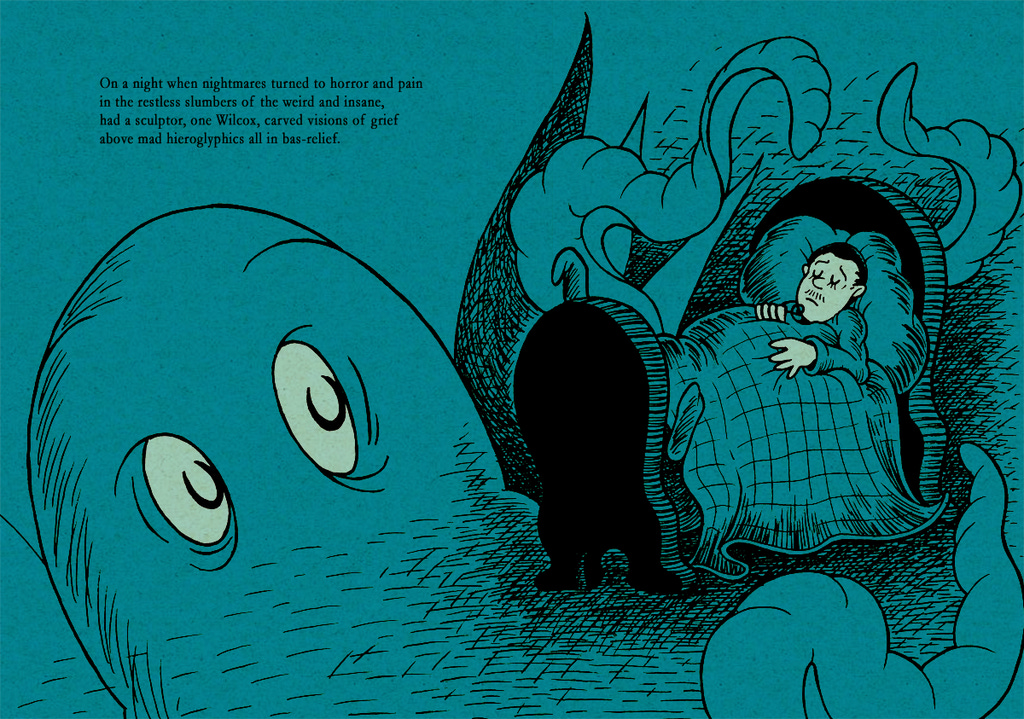

This is the sort of vacuum that demands meaning be injected into it, and the sort of gnostic myths that Lovecraft put into his work fit well. The content can be flexible; what matters is the idea that there is some sense to be made behind the veil of seeming everyday existence. To “know” reality may drive one mad, but one can still be certain that there is some overriding principle to the universe that goes beyond the quotidian nonsense that is both tedious and exhausting.

Alan Moore, that arch-rationalist mystic, implies the same:

And what Lovecraft seems to be doing in works like The Case of Charles Dexter Ward is attempting to embed the cosmic in the regional… He understood how this decentralised our view of ourselves; it was no longer a view of the universe where we had some kind of special importance. It was this vast, unimaginably vast expanse of randomly scattered stars, in which we are the tiniest speck, in a remote corner of a relatively unimportant galaxy; one amongst hundreds of thousands, and it was that alienation that he was trying to embody in his Nyarlathoteps and his Yog-Sothoths.

As an intellect he understood that that area around him was just part of a gigantic chaotic meaningless random universe. And I think that in his stories of transcoding horrors manifesting in New England settings he was trying to bridge the gap between the personal, intimate human world as we know it and the vast, inhuman cosmos as we know it.

Lovecraft is indeed a bridge, serving as a safe peek into the supposed other world. No matter how much time Lovecraft spends telling you how indescribably horrible something is, at the end of the day he still is plugging the void. Behold the reality behind the veil, the Fortean forces that shaped human history! That reality may turn out to be octopus creatures and invisible carnivorous demons, but what more could Lovecraft possibly offer than fairytales? The combination of the pretense to gnosis and an expandable, appropriable lore becomes appealing when this reality (the real one) loses coherence).

Houellebecq downplays the gnostic aspect of Lovecraft yet effectively endorses it

HPL’s writings have but one aim: to bring the reader to a state of fascination. The only human sentiments he is interested in are wonderment and fear.

If I’m right that Lovecraft’s popularity reflects an ascent of gnosticism that kicks in whenever there’s a dearth of coherent social meaning available (no matter how scary), then he’s ultimately a life- and meaning-affirming writer who gives comfort. If “Lovecraft’s works stand against the world and against life,” as Stephen King puts Houellebecq’s thesis, it’s because they offer the possibility of something better, no matter how horrific. Whether it’s the Elder Gods or late capitalism, the hidden forces of the world give it meaning that the explicit causes no longer provide.

Ultimately, though, it’s all this world, no matter how we may try to separate it out, which is why Mark E. Smith’s jumble of B-movie trash is the best invocation of Lovecraft I know:

MR James vivant, vivant

Yog Sothoth, Ray Milland

Van Greenaway, R Corman

Sludge hai choi choi choi sanThe Fall, “Spectre vs. Rector”