The Modern Subject No Longer Exists

Neither does the postmodern subject for that matter

A friend asked me about works on “the modern subject,” and I said it no longer existed. He asked why, and this is my answer.

The “modern subject” is the idea of some unified, continuous, narrative and narrating “I” that organizes and runs the show of every human being. Some people call it the “Cartesian subject,” which is a real misnomer if you read Descartes, but the idea and the history of the idea twist its way through the last few centuries of all the humanities.

If you read Bruno Snell’s wonderful Discovery of the Mind, you may be convinced that the idea of a “modern subject” goes much further back, to classical Greece at least, but as a subject of debate, it was only in the last 19th and 20th centuries that it came in for serious dispute. In the 20th century it was thrashed from multiple sides, the idea of a unified and autonomous subject being deem culturally constructed, misleading, nonexistent, a pervasive illusion, anachronistic, and worse. If Heidegger and Daniel Dennett are both weighing in against a concept, it must be a pretty pervasive concept, and the sheer amount of the criticism only shored up just how enduring the idea was.

You could argue that Freud was the first person to give it a significant public beating by successfully injecting the idea of the unconscious into popular and less-popular discourse, cordoning off part of the subject into a realm that was neither directly addressable nor controllable. It doesn’t seem to have been a fatal blow, since most believed that the unconscious could be contained and incorporated into a revised idea of the subject. Still, speaking of different parts of the mind with different motivations and processes sets the ball rolling to dissolve the human mind into something with no integral subjective core.

This in turn led to what led to what’s sometimes called the “postmodern subject,” where a certain subset of academics theorized the dissolution and fragmentation of identity while going about their daily lives just as any other modern subject had gone to. There are sincere exceptions to this sort of hollowness: neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland genuinely speaks and acts with a convincing lack of belief in her own subjectivity, but her atypical example only shows how rare it is. For the most part, the theoreticians of the “postmodern subject” have only played games with terminology, and the modern subject has gone unchallenged.

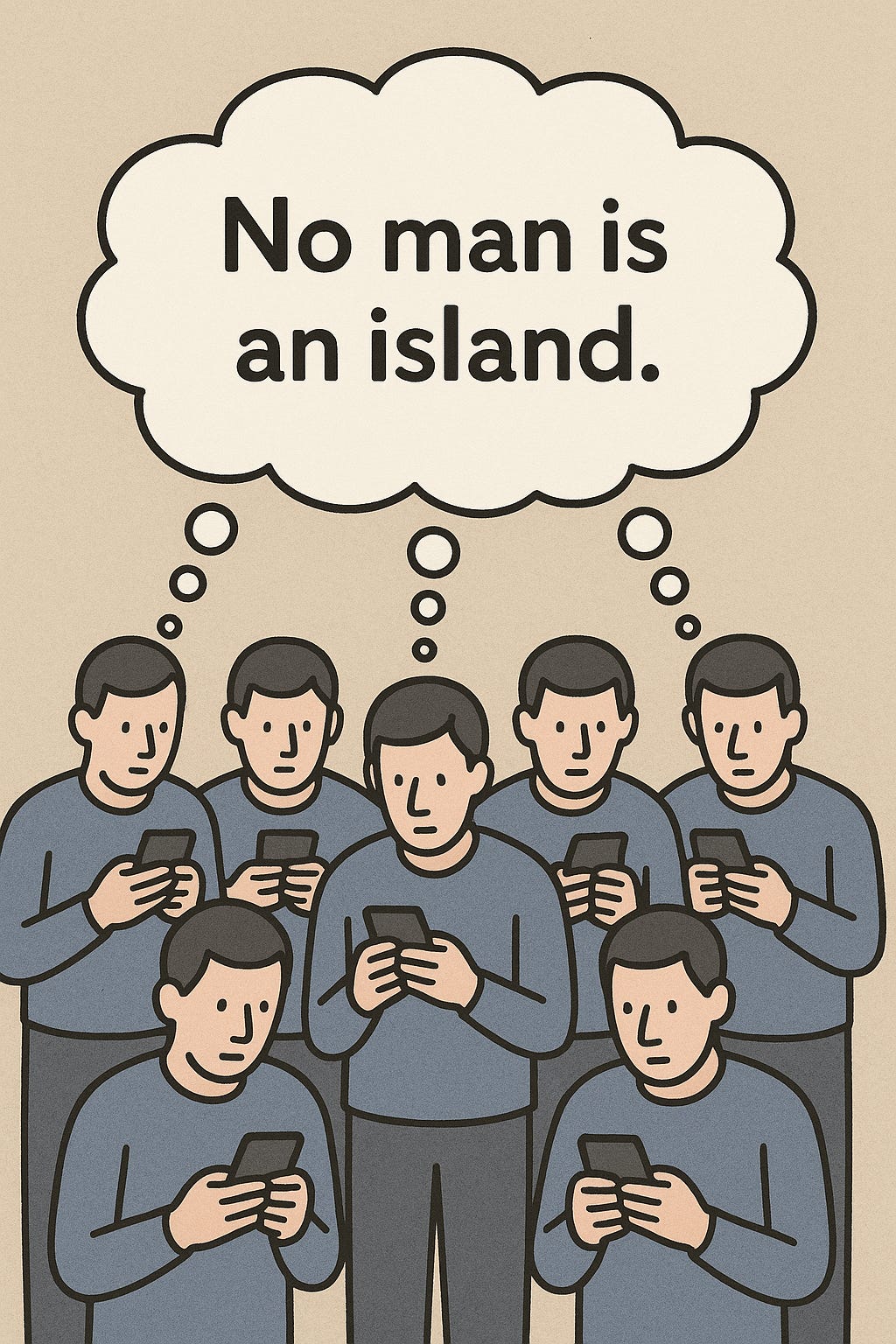

And yet, here I am claiming the modern subject is finally meeting its death—at the hands of hypernetworked society, algorithms, and AI. Why this time for real? From my perspective, the modern subject was an artifact of societal organization, and as long as we were individuals walking around embodied as blatantly discrete entities, there was little that could change the basic concept of the autonomous human agent, no matter how historically determined our actions might have been.

What always-connected culture did was to finally allow for the real creation of hiveminds. Associations could now be generated and reinforced at an exponentially greater speed and force, replacing the common, elite-driven mass cultural background with thousands upon thousands of far more specific, curated ones. The classic presentation of this change is Tonfreed’s Toaster Fucker Problem:

I blame the internet. Back in the days before it, we had to learn to live with those around us, now you can just go out and find someone as equally stupid as yourself.

I call it the toaster fucker problem. Man wakes up in 1980, tells his friends "I want to fuck a toaster" Friends quite rightly berate and laugh at him, guy deals with it, maybe gets some therapy and goes on a bit better adjusted.

Guy in 2021 tells his friends that he wants to fuck a toaster, gets laughed at, immediately jumps on facebook and finds "Toaster Fucker Support group" where he reads that he's actually oppressed and he needs to cut out everyone around him and should only listen to his fellow toaster fuckers.

Apply this analogy to literally any insular bubble, it applies as equally to /r/thedonald as it does to the emaciated Che Guevara larpers that cry thinking about ringing their favourite pizza place.

It goes further than Tonfreed says. In Meganets, I wrote about this social coalescence from the perspective of ideology and groupthink, but it goes deeper to the fundamental level of identity.

Insular bubbles have existed since time immortal, but short of actual communal cults, even the most insular bubbles still required their members to spend time outside the bubble. It didn’t even have to be with other people—just spending some time alone was enough to preserve some degree of differentiation with others.

The modern subject doesn’t die, and the hivemind doesn’t exist, until people internalize their bubble to such a degree that they feel it within them, looking over their shoulder and advising them, seemingly in the form of a smartphone but actually in the form of other people’s psychological presence. Hold on to that feeling long enough, and you can no longer fundamentally distinguish between what you are as an individual and your function as part of a persistent and ubiquitous hive (or two or three) of people. You may have a unique and distinct role within that hive, but you are no longer a subject.