When Gavin Newsom vetoed California’s “AI Safety” bill today, the response was mostly confused, even from Newsom itself. Big Tech definitely didn’t want it, far more than they didn’t want the other bills Newsom recently signed. Newsom’s rationale was the bill was just too massive and vague: “I can’t solve for everything. What can we solve for?”

The bill’s defenders haven’t exactly contradicted that. The point of all these bills to get something—anything!—into regulatory practice. As the Brookings Institute puts it:

California legislation does not need to be a perfectly comprehensive substitute for federal legislation—it just needs to be an improvement over the current lack of federal legislation.

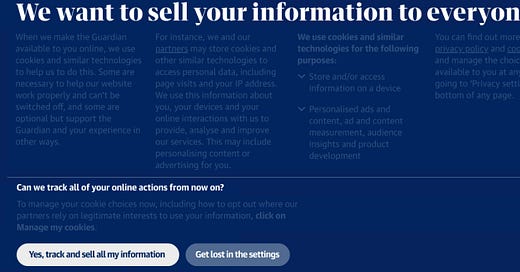

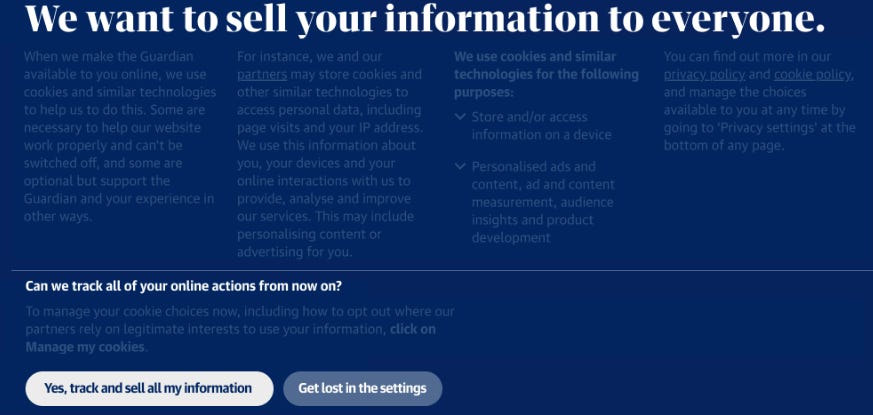

And there’s a point to be made here. But for every serious bill like one requiring data transparency, there are a dozen that amount to barely more than mandates for obfuscatory consent policies like the ones for cookies:

In a regulatory frenzy, the politician’s syllogism often takes over: “We must do something. This is something. Therefore we must do it.” In the case of cookies, regulatory frameworks for online privacy have, from my point of view, done very little to stanch the bleeding of public information. Ironically, the most significant privacy initiatives have come from big players like Apple and Google implementing tighter privacy controls in order to squeeze out shadowy data brokers who are considerably more invested in microtargeting consumers and reselling the data than the big players.

I am not anti-regulation, but in practice, the efficacy of regulatory regimes correlates closely with widespread understanding of what’s being regulated. Even then, the FAA’s inability to regulate Boeing into making their planes safe make you wonder if even older regulatory regimes are only discovered to be grossly inadequate when something as public as an airplane crash happens. Still, given the complexity of AI and its intrinsic opacity, any regulatory effort needs to begin by recognizing that this is one of the toughest regulatory challenges ever faced.

My momentary brush of fame as a journalist came in 2013 when I watched the Healthcare.gov hearings and wrote a few articles saying, basically, that no one knew what they were talking about: not the government contractors, not the members of congress, not the Obama administration officials. In 2013, there was still a certain kind of mystified reaction among certain cultural elites to technology, and I was a temporary beneficiary of that reaction. Subsequently, cultural forces came into existence that convinced such elites that they now knew enough.

What I learned was that the process of cultural absorption of new technologies and unfamiliar phenomena doesn’t go from ignorance to knowledge, but from anxiety to conventional wisdom. Or to put it another way: from knowing that you don’t know to not knowing that you don’t know. Call it a Reverse Socrates.

A similar process is happening now: AI has come onto the scene and there is a recognized knowledge vacuum: we all know that no one knows what’s going on with it. Even the experts are arguing over what the risks are and what to do about them, as with last year’s failed push for a temporary moratorium on large-scale AI development.

In this sort of environment, any regulation will inevitably be little more than a beachhead, since no one can even agree on what the regulations should be. AI is doubly opaque, first in the intrinsic mysteriousness of its workings, and second in the secret sauce applied by the biggest AI developers—OpenAI and Google chief among them. It took years for the FTC to settle the comparatively simple matter of whether Google favored its own properties in its search results. Now imagine what might be involved in policing AI, where there won’t be paper trails of corporate intent, but only layer upon layer of impenetrable deep learning.

This is all to say that there is no agreement on how to regulate AI, nor even feasible suggestions as to how it could be done. But the Reverse Socrates process means that increasing numbers of people will claim to know how to do so. Who will end up doing so? I believe the situation heavily favors the tech side. The people with the best knowledge are, of course, employed by AI companies. You have a handful of detractors and apostates like Gary Marcus and Geoffrey Hinton, but they will be the last people involved in the regulatory regime. Regulatory experts such as Tim Wu will get involved, but they will be at a disadvantage from lack of insider knowledge. The Reverse Socrates crowd will probably get a foot in the door but will eventually be filtered out.

Ultimately, regulatory capture seems very likely, a Vichy regime controlled indirectly by the tech companies themselves, offering strong, biased, and inadequate advice on how best to police themselves, which will be taken in the absence of any other available knowledge. When their advice proves inadequate (as it inevitably will), there still won’t be anyone else to turn to. AI—specifically huge-scale deep learning—is possibly the most regulation-resistant technology ever developed.