Quantification of Virtue

A case study in measuring goodness computationally

Computers deal with quantified data—even in AIs, which can hide the quantification under layers of opacity, the underlying mechanisms remain computational.1 I’ve written elsewhere about how the metaverse is going to push the quantified self into the realm of the gamified self—where all that measurement isn’t just for tracking, but for competition.

Viral competition has already proven to be a moneymaker: at one point, Facebook drew 30% of its revenue from Zynga’s Farmville and its clones, games that exploited social competition to encourage users to pay for virtual crops. Roblox and Decentraland are blueprints for how Meta and Microsoft hope to turn the whole world into Farmville.

The result will be the monetisation of identity, something already visible in the burgeoning industries of paying for instruction on how to be patriotic, how to be anti-racist, how to be Christian, how to be eco-conscious. The metaverse seeks to make money off of less-loaded aspects of identity by fostering intra-group solidarity through purchases. As sociologist Erving Goffman wrote, “To be a given kind of person, then, is not merely to possess the required attributes, but also to sustain the standards of conduct and appearance that one’s social grouping attaches thereto.”

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has more or less said that their planned purchase of Activision Blizzard is directed exactly at gamifying online life. So it’s worth looking very closely at how computer games have quantified aspects of human existence, as a preview of what awaits all of us.

Dungeons and Dragons remains the pioneering example, boiling player activity down to a handful of simple statistics managed in arithmetic. Whenever games have attempted to make such D&D-inspired stats too elaborate, they’ve garnered player complaint because transparency is essential to such assessments: players want to know why they succeeded or failed at what they did, and any mechanism that goes beyond arithmetic is going to become too opaque to grasp quite quickly.

So even 50 years after D&D’s creation, the general model of arithmetic stats remains more or less unchanged, applying both to physical and non-physical traits. Most advertiser profiling is based on tags given to consumers based on past activity—not so different a system. Even reigning titan of complexity Dwarf Fortress keeps a lid on the psychological modeling of its NPC dwarves by dealing with a primitive survival situation and primitive needs and emotions—and even there it already struggles to contain the complexity, in creator Tarn Adams’s words:

There's not a lot to a dwarf's psychological makeup right now, and that's something that we really want to change, because it lets you not just control things like tantrum spirals - stuff that are side effects of the system that you need to have a different system to really control well, and control in a reasonable well - but having a better system would let you look at the dwarf and not just say 'hi, I'm happy' or 'hi, I'm sad', but it would actually tell you a little bit about what's going on in the dwarf's head…Overall they could have a baseline emotional state, some people are just generally happier than others, and the events could tweak that, push you slowly in one direction or another, so you could become miserable as things keep happening to you. But getting rid of that happiness number entirely and just having the emotional state of the dwarf on several axes would be a lot better way of handling it…I want to keep the personality facets, I like having the thirty different facets of the personalities, and just increasing the overall number of places those are used. But I think to complement the personality facets we also need stuff like different emotions that you can be feeling, and additionally some things along the lines of those likes and dislikes, but stuff that the dwarf could be into, or the dwarf's vices or something like that; some kind of more permanent characterstics, but that can be changed through exposure; just to give them more texture there. But happiness numbers are definitely going to go.

So what happens when the quantified subject gets really loaded, as with ethics? If anything, games tend to play it even more simply when it comes to morality, because if players dislike it when they win or lose a battle and don’t know exactly why, they really are bothered when their character is deemed good or evil without them having intended to be such. “Good” and “evil” actions have to be clearly telegraphed to the player as such, so that the subsequent effects on in-game reputation follow expectations. Simplicity is the price for such moral transparency.

Yet more than simplicity, it also leads to arbitrariness. Whether or not the “metaverse” succeeds, the digital mirrors increasingly being constructed by and for people are going to track ethical and quasi-ethical matters as much as they track habits, health, activities, and demographics, and algorithms will pass summary judgments on everyday activities, even unwittingly. They may not be the most consequential judgments, but especially with the increasing gamification of online (and offline) existence, the tendency toward evaluating behavior not only on a quantified basis but on a quantified moral basis will increase.

One case that’s come up in recent years has been China’s Social Credit System, which has been portrayed as a potential Big Brother AI rating your moral virtue on a day by day basis. The irony is that the Social Credit System is considerably less than it’s billed as, more a paper tiger designed to keep people in line than a mechanism that actually polices everyday behavior. It does act as a blacklist for Chinese citizens who refuse to pay fines and express open dissidence, but worries of buying too much liquor branding you as an alcoholic are, for the time being, fairly speculative.

These sorts of judgments are less likely to come from the government, in fact, but more from emergent evaluative systems of privately operated networks—like games. Ethics won’t be governmentally adjudicated, but will be a matter of metrics that attach to you within various online contexts on those private networks.

We are already classified demographically and microtargeted; the next phase of online life is for such classifications to not be between business and consumer but within social groupings, metrics often shared for “fun” but with a more loaded normative force. Think of the Myers-Briggs personality types, already used as convenient shorthand by many, backed by one’s digital footprint. Instead of taking personality tests, your increasingly elaborate digital twin will be used to generate results automatically.

I don’t even mean “transgressions” in that strong a sense, but imagine one’s behavior amounting to a profile in the same way that one’s credit card purchases do. If the everyday interactions that today go forgotten are stored and archived whenever they occur online, if one’s social media activity is coalesced across all sites (as it inevitably will be) into a record of one’s overall personality tendencies, there will inevitably be a moral component to algorithmic assessments made of such behavior. Likely these assessments will go through AI-based mechanisms, secretly or not secretly classifying a person in taxonomies like the Big 5 personality traits, or Dark Triad tendencies, or you name it.

Whatever pretense these classifications have to be morally agnostic, in truth they will classify us ethically (either implicitly or explicitly), at home, at work, and at play. It will not be so crude or so draconian as a single moral score; such assessments will frequently be more complex and more open to interpretation, seen more positively in some lights than in others. But moral they will be.

The results, however, will not be valid, even though we will usually take them to be.

My case study here is in the very popular RPG Divinity: Original Sin II, which cagily admits to the problem in an almost-throwaway manner. The game is a standard high-fantasy story that disposes with D&D’s always-perplexing two-axis moral alignment system (good vs. evil; lawful vs. chaotic) and more or less allows you to be as good or bad as you want to be, but there is one exception to its moral lassitude. (And here I am grateful to fanatical players who delved far, far deeper into the game than I ever could.)

Toward the end of the game, you need to get into a secret tomb by going through a test called “the Path of Blood,” an extraordinarily stringent moral evaluation that instantly kills you if you’re found wanting. Two of the criteria for failing (there are others) are (1) do you steal, and (2) do you kill? Almost any player will find the answers to those questions to be (1) yes and (2) very yes. There is no way in hell you will meet the given standard if you have played the game in any non-pathological way. If you do take the test in the game, you will fail it and die.

There’s no prior warning that you’ll have to pass such a test, but it really doesn’t matter. The real solution is to find the designer of the test and learn the backdoor to bypass the evaluation—which doesn’t require any moral purity whatsoever.

As a satire of absolutist RPG morality (and absolutist morality more generally), it’s cute. What’s downright clever, though, is that it is possible to pass the test. Devoted (and devout) players spent an inordinate amount of time figuring out the exact criteria, since the slightest deviation immediately and permanently brands you an impure sinner. There are a couple of one-way flags that track any deviation from impurity:

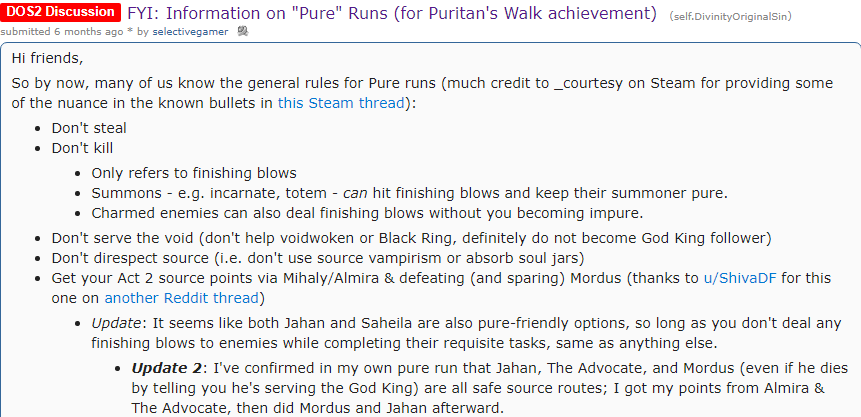

But what does it mean to steal, or to kill? Wars have been fought over that question, but the game has to take a stand. Inevitably, the criteria are fairly arbitrary, as selectivegamer summarizes:

Determining just how arbitrary required black-boxing the game and testing various scenarios at tedious length:

You can, it seems, literally make a deal with a demon and still remain pure—as long as you delegate the actual deathblows required by your part of the deal to others.

Obviously, this is all ridiculous. It’s not nonsensical, but the game designers clearly realized the absurdity of delineating moral responsibility in such a stringently binary way and decided “In for a penny, in for a pound.” They consciously made the moral judgment calls above, but they did not take them seriously as real ethical guidelines. You have to go through the trouble of bashing people almost to death and looting graves to discover that they don’t taint your character’s purity—but that sort of black-and-white morality is indeed baked into this obscure little cul-de-sac of the game.

So the satire extends to the structural level of game design, by putting forth an in-game ethical goal that is nearly impossible to meet and is completely unnecessary to meet—in order to spoof the very idea of doctrinaire moral guidance.2 The "reward" for passing this ridiculous test is appropriately absurd: after remarking “This statue is a fine judge of character," your character gets wings and permanently glows.

The problem is that when it comes to quantification of virtue, there’s no clear alternative to the ridiculous. It’s cute for a game to punt the issue into the realm of the absurd, but only slightly less absurd (albeit far more forgiving) quantitative mechanisms really will emerge as we quantify our lives more thoroughly. They won’t be as draconian or as panoptical as various dystopian nightmares have portrayed it. If anything, people will probably be a bit generous given the awareness of the systems’ inadequacy. Yet like the MBTI, there will be an impact, and we’ll have a bunch of new algorithmically-generated descriptors telling people who we are—morally—before we ourselves get the chance to.

One way to preserve the qualitative experience, however, is to increase complexity and opacity beyond human comprehension. It’s possible that this is exactly how the brain and “mind” achieves their seeming qualitative properties.

Jonathan Blow did something analogous with the “eight stars” of Braid. And yes, Undertale did too.

With the reporting on social media being able to predict pregnancy before the user does and advertising items based on mood gleaned from their recent posts, I would not be surprised if there are studies behind social media's closed doors to predict even more. Especially considering the large amounts of money they make from selling big data to advertisers.

I am behind on the literature, but I wonder if there are groups, both private or public, trying to operationalize social media posts and other online behavior to align to the popular personality test or other psychological assessment results like you had mentioned. Based on the whistle blower hearings with Facebooks's whistle blower, Frances Haugen, a lot of research is done by social media companies is being done behind closed doors and is not made public. How would people feel if they knew their social media platform was running psychological assessments and then selling that data to advertisers and other businesses with interest in then information, if this became a thing? There are currently issues with privacy with the current models of big data collection harvested by tech industries. How much more of an issue will privacy become before legislation is in place to protect folks? It is definitely an interesting topic.

On a side note, I feel like the "monetization" of games is really wrecking old games I have loved growing up. Seeing Diablo turned into a "free" mobile game with $100,00 plus ways to spend money to progress and get items in game, after the Activation take over and game designer exodus, really ruins it for me. Magic players talk about the product fatigue and the $999 dollar booster packs of fake cards for the 30th anniversary. The OGL situation in D&D was a huge blow to us third party and indie creators. I think when profit comes before fun, it really shows in a negative way for their products. Learning about what behavioral data and analytics they are pulling from players will be interesting. Hasbro mentioned during one of their corporate meetings mentioned data collection and D&D Beyond, but didn't get into the specifics regarding what kind of data they were collecting nor the depth of that data collection. I really like the point you made regarding the companies looking at competitive behaviors when designing these games and trying to maximize on them. It will be interesting to see what path big data and the gaming industries head down.