If the defining trait of “wokeness” is a persecution narrative, then we really are all woke now. The run-up to this election has seen every faction and interest group claiming victimization at the hands of some oppressor, but without any agreement of who the real oppressor is: is it the Deep State or the Supreme Court? Is it immigration or nativism? Is it the 2025 Project or the Open Society Foundation? Is it Elon Musk or Mark Cuban? Each polarization gets mapped on to either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris, however well it fits, and to a partisan on one side, everything on the other side becomes the enemy.

Each side is convinced that they’re fighting a rear-guard action against terrifying, larger-than-life forces with resources far beyond their own. Actual politicians are squeezed between classic venality and the encroaching fringe-dwellers, marking the true end of the party machine. Party machines can only exist when realpolitik dominates over persecutory purism. That trend began to reverse with the collapse of Southern Democrats in 1994 and, with a few brief hiatuses, has continued since then.

Few seemed to notice it at the time because the persecution narratives were developing so independently, but parallel processes were emerging on both sides. In the 1970s and 1980s, just as the Southern Strategy stoked resentment to fuel more white Republican votes, Peggy McIntosh set out the blueprint for what’s now termed the leftist “woke” ideology of privilege and hegemony.1 There were stark differences: the Southern Strategy was explicitly a Republican movement, while McIntosh worked within a leftist academia that, at the time, was quite alienated from the majority of the Democratic party. Yet both set up similar persecution narratives.

Subsequently, Rush Limbaugh-style talk radio and Fox News amplified the right-wing persecution narrative top-down, bellowing about Wars on Christmas and forced gay marriages as the left-wing persecution narrative spread more organically through academic, online, and bureaucratic channels, until we ended up where we are today.

The right-wing persecution narrative reached its apotheosis in Donald Trump, who uncannily embodies petulance-as-strength as few can. An attack on him is an attack on all of MAGA. The left-wing persecution narrative is more amorphous because its emphasis on marginalization means that its leaders have to speak on behalf of “silenced” groups, and so what emerges there is a series of iconic victimized figureheads and oppressed populations for which the vocal left professes to speak. But the underlying persecutory complexes are structurally the same, whether it’s “colonialism” or “immigration” that is the principle around which persecution forms.

And indeed, vague concepts like colonialism, capitalism, communism, and equity become the signifiers for the causes of oppression. To paraphrase Hans Blumenberg, it’s the sheer vagueness of these persecutory complexes that allows them to be so flexible. “Discontent [e.g., persecution] is given retrospective self-evidence.” This is what allows for the ostensibly freedom-fighting Republican party to shift to an isolationist, protectionist stance under Trump without much notice, even as the ostensibly anti-billionaire Democrats loudly put up billionaires JB Pritzker and Mark Cuban to speak for them. The internet has been an unprecedented boon for such vagueness, disconnected words from actions and policies while providing far more avenues for hysteria than tranquility.

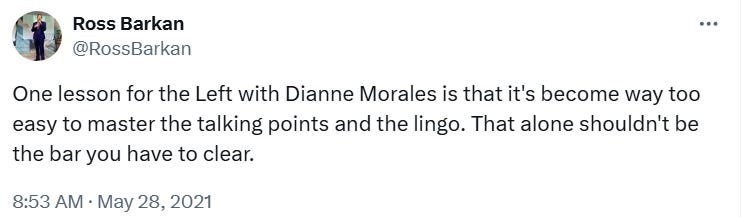

The problem is hardly confined to the left. Online, only the lingo matters—and way too much of life today is online. The all-or-nothing commitments demanded on both sides means that taking either side commits you to a maximalist version of that side’s victimization narrative and a carte blanche commitment to that side’s actions: that is what makes us all woke now. Who is victimized is always “us;” how can change on a dime.

George Orwell was mistaken to think that the best scenario for committing a group to ideological uniformity was a top-down totalitarian regime. Having two opposing sides, neither definitively stronger than the other, each in plain sight of the other, works even better to keep people in a state of fear that any slippage or deviation from their side will be the breaking point and lead to permanent defeat.

Whoever wins tomorrow, it is guaranteed that both sides will see themselves on the “losing” side to some degree, either having lost ground catastrophically or at best having temporarily staved off a devastating defeat. There will be plenty of convincing “evidence” as to why this is true.

I don’t believe a state can remain functional in the face of this sort of race-to-the-bottom agonism, but one’s view is increasingly impaired these days. There is undoubtedly a growing faction of exhausted people who see the dueling-victimization as useless and would prefer peace and quiet over taking either side, but the upshot of that sentiment remains to be seen. Most likely, the victimization competition will continue to degrade civic life until some unexpected crisis, significantly bigger than COVID, forces a more drastic realignment, for better or for worse.

Theoretical note: I single out McIntosh because, unlike the writings of many social theorists of that period, her vulgarization of post-Marcusean theory was populist, accessible, and required a minimum of cognitive effort to grasp. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” is far more influential prototype for left “wokeness” than the collected works of Marx, Adorno, and Butler together. I have written extensively on this.

Agree. There is only one way out: getting out of the binary Left/Right (and, of course, oppressed/oppressor). As long as we think of the life of the polis in these terms we are doomed to replicate this pattern. But: easy to say, hard to do. Still, try we must. The first step is for the intellectuals to avoid thinking in these binary terms--after all, they control the media and discourse.